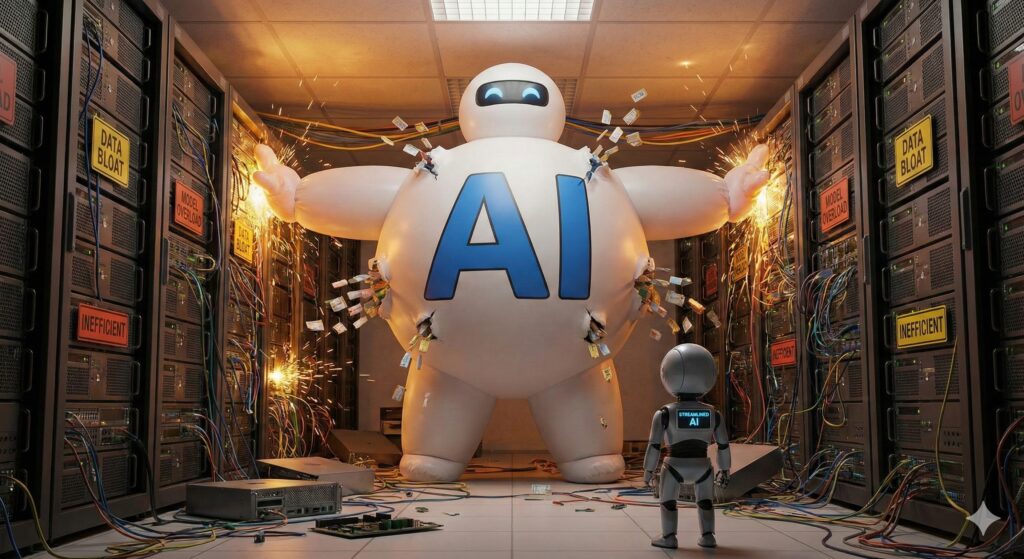

The Next AI Failure Mode Isn’t Hallucinations. It’s Bloat.

By Mike Schumacher, Lakeside Software

A funny thing happens when you give a smart system more information than it can comfortably use: it starts acting less smart.

Most of us have seen this in normal life. You clean the garage, get excited, and decide you are going to organize every tool you own. Then you buy more bins, label everything, and end up with a space that looks impressive but takes longer to work in. The workbench disappears under “helpful” organization. The signal gets buried under the effort to manage the signal.

AI is starting to hit the same wall. And it has a name: context rot.

Traditionally, when people talk about “rot” in enterprise IT, they usually mean staleness. In fact, when I initially explained the outline of this article to some of the folks on my team, they thought I was talking about knowledge base articles that no longer matched reality or runbooks that reference systems you migrated off two years ago. In other words, documentation that ages faster than whatever it’s documenting.

That problem is real. But “context rot” is different.

Context rot is what happens when an AI system is trying to solve some reasoning task, and we keep feeding it more and more input in the name of being thorough: more chat history, more tickets, more KB articles, more logs, more telemetry, more “just in case.” When the output of the reasoning flow misses the mark, the system is not failing because the inputs are out of date. It’s failing because there are too many of them.

The result is counterintuitive: the AI can become worse at reasoning precisely because it is paying attention to too much.

The hidden math behind “more context”

Under the hood, many modern AI systems behave like very capable readers with a limited desk. They can spread out a certain number of pages and do great work. But once you keep stacking more paper onto the desk, the reader spends more time shuffling pages than thinking.

There are two practical reasons this gets ugly fast.

First, there is compute cost. With transformer-style models, the work of processing a longer context window tends to grow roughly with the square of the number of tokens. In plain English: doubling the amount of text can cost you a lot more than double the compute. So “just add more context” is not free, it’s a tax that compounds.

Second, there is attention dilution. The more you stuff into the input window, the easier it is for important facts to get lost among irrelevant facts. In long prompts, models can show positional bias: they may overweight what is most recent, or what is at the very beginning, and underweight the messy middle. So the AI is not just slower and more expensive, it’s also more likely to miss what matters.

If you have ever watched someone do “research” by opening 42 browser tabs and then forgetting what they were trying to learn (count me among the guilty), you already understand context rot.

The enterprise self-service helpdesk version looks like this:

- A user has an issue on a laptop.

- The AI helper is asked to diagnose it.

- We give the AI the last six months of tickets, five KB articles, the entire chat transcript, the device inventory, the event logs, and a telemetry dump.

- The AI responds with something that sounds confident but is oddly generic, or it latches onto a recent detail that is not causal, or it parrots the most recent KB excerpt as if recency equals truth.

We then conclude, “AI is not ready,” when the real problem is that we built a system that cannot separate the signal from the noise at scale.

Knowledge bases can be part of the problem

I have never been a fan of knowledge bases because of the classic definition of rot: they often become stale faster than the rate of change of the thing they’re documenting. But KBs are also a perfect ingredient for context rot if we use them the wrong way.

If your AI system is built to pull in every “related” KB article, plus every “similar” incident, plus every “might be relevant” snippet from Slack or the collaboration tools of your choice, the context window becomes a landfill. The AI now has to reason while standing knee-deep in shredded paper.

This is the hard part: in the moment, the behavior feels responsible. No one wants the AI agent to miss something, so teams keep adding more context as a form of insurance. But the insurance premium becomes the failure mode.

At a certain point, “thoroughness” is indistinguishable from “pollution.”

Why this gets worse as AI gets more capable

There is another twist.

As AI systems get more capable, we ask them to do bigger jobs. We want them to not only answer questions, but also to own “flow.” We want them to troubleshoot, remediate, document, and escalate across several tools.

That, by design, pushes teams toward increasingly bloated prompt payloads. More history, more artifacts, anything that might be responsive to the workflow’s theme.

Which is exactly how context rot sneaks in.

If we keep feeding the LLM anything remotely topical to its flow, we will end up with AI that is expensive, slow, and surprisingly mediocre at the moment you need it most.

So, what does “done right” look like?

The alternative: stop stuffing the foreman’s clipboard

A mental model that helps is to think in terms of a foreman and skilled trades.

In a well-run job site, the foreman does not personally do electrical, plumbing, framing, drywall, and HVAC. The foreman coordinates. The trades do the deep work in their domain, then report back what matters: what they found, what they recommend, and what they need next. The foreman then vets the outcome.

AI systems should work the same way.

Instead of one orchestrator model carrying every detail in its context window, you break the work into sub-agents (or specialist components) that operate with narrow scope:

- A diagnostic sub-agent that can look at device telemetry and summarize anomalies.

- A policy sub-agent that interprets what has been deployed and what is allowed in that environment.

- A knowledge sub-agent that understands the ebb and flow of the user’s historical interaction with their device and returns only the handful of steps that match the current symptom pattern.

- A remediation sub-agent that can run a bounded set of actions safely, with verification steps.

- A guardian sub-agent to vet the output of the remediation sub-agent and provide a risk assessment.

Each specialist can have its own “context window,” sized to the job it is doing. It can consume the noisy detail because that is what it is built for.

But the orchestrator, the foreman, should stay clean. The orchestrator should receive summaries, conclusions, and evidence, not raw dumps.

This design does three things at once:

- It prevents context pollution in the place where planning and reasoning need clarity.

- It reduces compute waste by limiting what the top-level model has to ingest.

- It scales better as the number of skills and actions grows, because specialists can be added without ballooning the orchestrator’s prompt.

In our work at Lakeside, we think about this as a core architectural requirement for AI in IT operations: keep the orchestrator lean and push the “dirty work” down into specialized agents that can prove what they found and why.

Practical guardrails to prevent context rot

If you are an IT leader evaluating AI tools, here are concrete questions that cut through the demos:

1) What goes into the orchestrator’s context window, and why?

If the answer is “everything we can find,” you have a context rot problem waiting to happen.

2) Do they bound context by design, or by accident?

A hard limit is not a strategy. A strategy is deciding what belongs at the top level, what belongs in specialist analysis, and what should never be in the prompt at all.

3) How do they handle long histories?

Do they summarize with an explicit freshness model, or do they just append more text? Summaries should also have expiration and verification. Otherwise, you are just compressing garbage.

4) Can they show you evidence, not just an answer?

Specialists should return not only conclusions, but also citations, signals, and tests performed. If you cannot inspect the “why,” you cannot trust it.

5) Do they test performance as context grows?

A surprising number of systems perform well on short prompts and degrade quietly at long prompts. You want vendors who measure that, not vendors who discover it in production.

The bigger point: enterprise AI needs an operating model, not a bigger prompt

I am optimistic about AI in the enterprise, especially in IT operations and digital employee experience. But we are in a phase where teams are confusing “more context” with “more intelligence.”

They are not the same.

More context can be helpful up to a point. After that point, it becomes a drag on reasoning, a cost bomb, and a reliability problem.

I believe context rot is past the theory stage. It’s a leading cause for enterprise AI project failures.

The path forward is not to stuff the prompt harder.

It is to build AI systems with an architecture that respects limits: delegation, specialization, verification, and clean orchestration. That’s how we get agentic AI that stays smart as the world around it gets more complicated.

Michael Schumacher is the founder and CEO of Lakeside Software. Prior to founding Lakeside, he led the division as a director of software engineers at Cubix Corporation, where he directed product development. At Telebit Corporation, he oversaw the department as an engineer for network products.

Mike has long experience as an engineer in the field of software and has worked for ISO (International Organization for Standardization) and ANSI (American National Standards Institute) standards bodies, contributing significantly to technology development. He holds a master’s degree in information engineering from the University of Michigan.